Weeds are often depicted as Enemy #1 in the gardening world, especially the dreaded invasive species. However, one thing is never one thing, but many. Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu says, “the named is the mother of the ten thousand things.”

A weed is really just the wrong plant in the wrong place, after all.

Pervasive Invasive Species

There are many factors or influences which contribute to and affect the dominance of particular plant species. Hydrology, soil type and texture, pH, organic matter, animal populations –most notably deer (native) and earth worms (non-native)—all have a quantifiable impact on the ecology and performance of a landscape. Our human tendency to look at things as black and white…problems with simple, actionable solutions may be incomplete when we try to understand complicated natural systems.

Take, for example. this newly promoted concept of Bio-Control Maintenance in the COVID-19 era. States like New York permitted the chemical maintenance –pesticides, herbicides, tick spraying– of properties as an essential service for health and safety, but prohibited installations of ecologically beneficial plants, the key to successful organic gardening (the installation ban has since been lifted).

In my opinion, reducing biological diversity as an answer to a problem is seriously flawed…we cannot completely control or predict nature! This may be true of weather, climate change, etc. By accumulating data, we predispose ourselves to expect a result supporting our belief and hypothesis.

A New Perspective on Invasive Species Management

One thing I know for sure in my lifelong career observing and working with natural ecosystems…things change!

For many years I worked with municipalities as well as contractors, designers, architects, engineers, professionals and homeowners to produce sustainable, manageable landscape environments. I have studied with highly qualified people in all our related fields, lectured extensively on native plants and ecological restoration, and I can say without reservation and in full confidence: there is no silver bullet for invasive plant species management.

Like our human bodies and nature itself, there are many factors contributing to the health and well-being of our complicated living systems and landscape environments.

For example, we describe the plant environment in zones delineated by hydrology and plant type, deriving communities such as wetlands, uplands, mesic, riparian, littoral, and palustrine. Understanding the environmental factors that allow plants to proliferate, or be overtaken, is essential in developing successful land management.

Human Development, Displacement & Disrupted Ecosystems: The Case of Japanese Barberry

To further consider factors that favor a particular species over another, we must consider human development and its impact on biological disturbance and displacement. A simple example is the effect of deer browse on the forest ecosystem and plant communities.

The result of lack of ‘control’ of deer populations has resulted in significant lack of diversity of and regeneration of tree species as well as all ground cover and understory species. You need look no further than a walk in the suburban nature preserves to see the dominance of Japanese barberry. This plant predominates as a monoculture because deer do not eat it, because of the plants’ large thorns.

Other concerning and self-advantageous factors: Barberry is allelopathic, meaning it exudes chemicals in the soil that inhibit the growth of other species. Barberry also greens up before the trees leaf out, taking advantage of the early spring sunlight to propagate prodigiously both by seed and clonal shoots.

While ‘control’ or suppression can be achieved by cutting and torching barberry, the real problem, the root of the issue, has been created by overpopulation of herbivores (deer).

Japanese Barberry’s Ecological Snowball Effect

The substitution of a diverse understory of native shrubs and perennials, with a monoculture of an exotic species has a ripple effect on the local ecology.

A study released last year from Washington State University and Great Hollow Nature Preserve and Ecological Research Center (in New Fairfield, CT!) measured the discrepancy in arthropod populations between native shrubs and barberry forests.

They found a 23% decrease in foliage anthropods and a 28% decrease in leaf litter anthropods in bnarberry-infested forests as compared to native understories. As reported by Phys.org Dr. Chad Seewagen, an author of the study describes the results:

“We saw a clear and concerning pattern of community simplification and trophic downgrading in areas that have been heavily invaded by Japanese barberry.

How these changes in arthropod community structure affect food availability, and the composition and quality of the diet of insectivores, like many species of birds, is something we don’t know yet. Much more work is needed to understand the full ecological impacts of this non-native plant that has overtaken so many forests in the eastern U.S.”

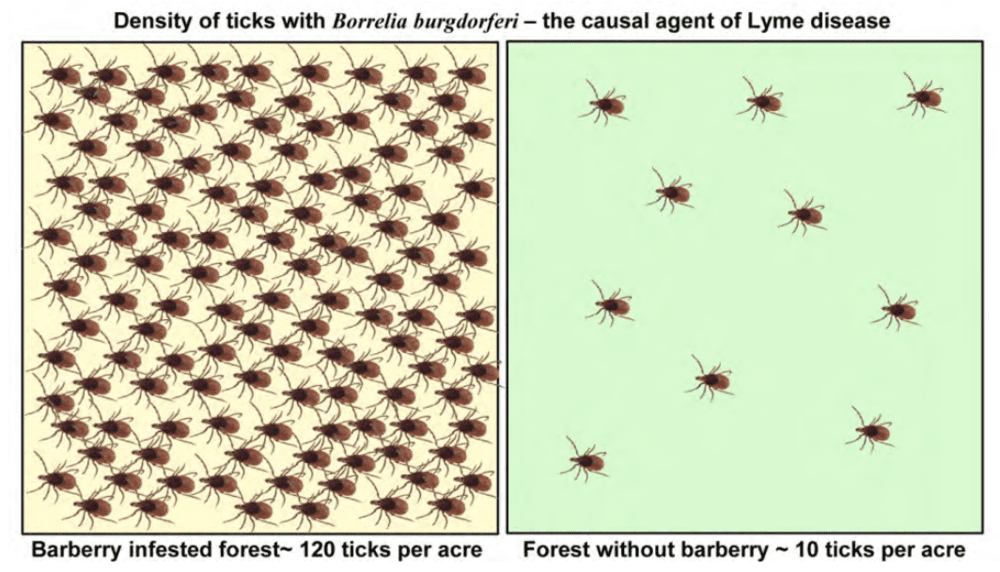

Another ecological impact of barberry: white-footed mice take shelter in the shrub (thorns are a natural defense), allowing their populations, as well as the ticks they often carry, to balloon. Ticks in the Northeast can carry Lyme disease, creating another human health concern associated with barberry’s overabundance.

Holistic Land Management for Invasive Species Control

Japanese barberry is not the exception; there are many such examples. Earthworms for another non-natiove example, have contributed to significant destabilization and degradation of soil conditions and biology resulting in substantial erosion of slopes.

In my work in managing invasive species in many Westchester County Park properties, results were mixed when no follow up planting (after invasive removal) or regular maintenance budget was provided to ensure sustainable results. It is a fruitless effort to remove unwanted species and not replace them with more desirable and ecologically valuable ones. Removal only opens the door to the weed seed bank and should be the first step in prescribed land management program.

The moral of the story is: success in controlling invasive species comes with designing a plan with a management protocol to deliver an acceptable range of results and expectations.

We must adapt to nature. It will not necessarily adapt to our changes in the environment in a beneficially predictable way. We need to analyze and inventory all site conditions and impacts on the landscape to develop a plan to alter the existing for the better, whatever that may be. Monitor, respond and steward with respect for the power of our precious natural resources.

Human knowledge, science and trust in our basic human goodness will all be required to create Landscapes for Better Living in this new world we are living in.

For more ways to get involved, check out the Lower Hudson Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management (PRISM).

Contact us about your land management or ecological landscape design project.

—

Jay Archer

Landscape Ecologist & Designer

Green Jay Landscape Design

914-560-6570